As a peace advocate, nothing can replace the experience of seeing firsthand the impact of violence on individuals and communities. While academic studies can communicate the social and public health consequences of conflict, only personal stories and images can communicate the emotional side of violence—the gravity of conflicts’ affects on the individual.

I came to Hiroshima on the anniversary of Japan’s surrender to the United States during WWII which occurred nine days after the world’s first atomic bombing. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial was teaming with Japanese gathered to commemorate the devastating attack on Hiroshima and who hoped to teach their children about the importance of peace.

The memorial site is comprised of a Memorial Park and Memorial Museum located on the grounds of the hypercenter of the bombing. At 8:15am on August 15, 1945, 600 meters above the city, the atomic bomb detonated, exhibiting one of the greatest advancements in human science of the 20th Century. The site of nuclear fission created temperatures of 3000 degrees Celsius, enough to burn and destroy nearly every building and life within 2 kilometers of the epicenter. Today, one partially destroyed building remains, known as the A-bomb dome, a lasting memorial of the destructive force of the acute effects of the bombing.

My visit to the memorial museum was particularly unique because I was traveling with a group of about 12 University of Tokyo students who peppered me with questions about how the United States educates children about the bombing, what progress Obama has made toward nuclear deterrence, and how I hoped to share the message of my visit to Hiroshima with those back in the United States. I was particularly fortunate to hear the testimony of a woman who was eight years old at the time of the attack, one of 200,000 individuals living in the city who managed to survive the acute affects of the blast and radiation. She shared about how she witnessed storms of people running with their arms extended as the skin melted off their bodies, the smell of burning hair that filled the city for days, and the many years of devastation and suffering that followed as the world learned of the full effects of nuclear weaponry. One story that particularly stood out to me was that of her childhood friend, an eight year old boy who watched as his mother died from burn wounds. In Shinto/Buddhist tradition, bodies must be cremated, but so many had died that the little boy could not find any combustible materials left in the area. He is still haunted today by the memory of only managing to cremate half of her body, a task that I could never imagine a child undertaking alone.

The children of Kids for Peace sent me with gifts for the children of Japan, especially those affected by the earthquake. One of their gifts was a beautiful 6-foot banner they painted, a tree of love that expressed the love they felt for the Japanese and wishes for peace, hope, and happiness.

The Children’s Memorial in the Peace Park contains a statue of Sadako Sasaki holding a paper crane, a young girl who died of radiation-related leukemia after folding over 1,000 origami cranes in hopes of a cure. Around the statue, individuals from around the world had created cranes of peace in sorrowful remembrance of the children who died from the bombing, and the museum staff felt that this would be the perfect location to house Kids for Peace’s banner.

The Japanese I spoke with all loved the children’s artwork and expressed deep gratitude for the children’s dedication to peacemaking. I was humbled to deliver the symbol of peace on their behalf, and promised to share the story of Hiroshima’s children with Kids for Peace children around the world.

Monday, August 15, 2011

Finding peace in Kyoto

The city of Kyoto is known as the epicenter of traditional Japanese culture, with more than 1600 Buddhist temples and over 400 colorful Shinto shrines. Kyoto, possibly more than anywhere else in Japan, has mastered the fusion of modernity and tradition, encouraging traditional dress while still maintaining an active business sector, high-rise buildings, and abundant western-style shops.

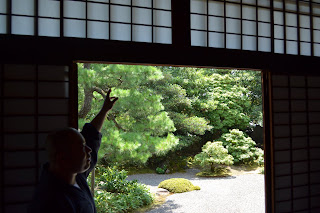

My visit began early in the morning, after the arrival of my overnight bus from Tokyo. My first stop was the Shunko-in Zen Buddhist temple. Built in 1590, the relatively new temple exemplified much of what has drawn me to eastern art over the years. The visual appeal of the dark wood details, contrasting white walls, luminescent shoji screens and verdant Zen gardens created an immediate sense of peace common in classic Zen architecture, while the gilded sliding door paintings by a Kano School artist depicted the social hierarchy, leisure activities, and intellectual elitism of the Japanese shogun and samurai.

My favorite part of my visit to Shunko-in was participating in a Zen meditation led by the vice-abbot of the temple. While I have meditated many times and was familiar with Zen practice, the monk’s simple explanations of routine forms brought new meaning to each custom. The meditation ended with a traditional tea ceremony which I enjoyed with my Japanese friends.

While I would love to spend more time in Kyoto, my day-long visit necessitated the selection of only a few key sights to see. I made my way over to Nijo castle next, the home of the Tokugawa Shogunate from 1626–1639. The palace is exemplary both for its ornate architectural details as and its well-maintained gardens where modern Japanese women sheltered under umbrellas recreate the feeling of Tokugawa geisha.

The apex of my stay in Kyoto was a late evening visit to Ninna-ji, a Shingon Buddhist temple founded in 888. My visit coincided with the Obon Festival, a three day celebration of the departed. As the sun set over Kyoto, huge crowds gathered at the base of the hill upon which the temple rests, all prepared with small messages and wishes to leave for their ancestors. At about 8:30pm, lights illuminated the temple structures and surrounding forest, and the visitors were allowed in to pay homage to the departed.

I have never seen a sight as breathtaking as the view from the highest structures of the Kiyomizu-dera complex just after sunset. The temple rests about halfway up a large hill, nestled delicately throughout the woods with an extraordinary view of downtown Kyoto. With every turn, visitors are greeted with an awe-inspiring vista set within an environment that encourages introspection and quiet meditation. I participated in as much of the festival as I could understand, drinking water from a wishing well and giving thanks for those who have gone before me.

My time in Kyoto was rounded out by an overnight stay in Ninna-ji, a Shingon Buddhist temple founded in 888. If you ever have the chance to visit Japan, I highly recommend staying in a temple. At Ninna-ji, I had my first Japanese bath experience (Japanese typically favor public baths over western showers), slept on a comfortable tatami mat on the floor of a large shared room, and awoke at dawn to witness the chanting of the Shingon monks in the main temple building. If I could begin everyday in such a meditative way, I have no doubt inner peace would follow throughout my day.

Up next, I will post about my experience visiting Hiroshima on the anniversary of the signing of the peace agreement between the US and Japan.

My visit began early in the morning, after the arrival of my overnight bus from Tokyo. My first stop was the Shunko-in Zen Buddhist temple. Built in 1590, the relatively new temple exemplified much of what has drawn me to eastern art over the years. The visual appeal of the dark wood details, contrasting white walls, luminescent shoji screens and verdant Zen gardens created an immediate sense of peace common in classic Zen architecture, while the gilded sliding door paintings by a Kano School artist depicted the social hierarchy, leisure activities, and intellectual elitism of the Japanese shogun and samurai.

My favorite part of my visit to Shunko-in was participating in a Zen meditation led by the vice-abbot of the temple. While I have meditated many times and was familiar with Zen practice, the monk’s simple explanations of routine forms brought new meaning to each custom. The meditation ended with a traditional tea ceremony which I enjoyed with my Japanese friends.

While I would love to spend more time in Kyoto, my day-long visit necessitated the selection of only a few key sights to see. I made my way over to Nijo castle next, the home of the Tokugawa Shogunate from 1626–1639. The palace is exemplary both for its ornate architectural details as and its well-maintained gardens where modern Japanese women sheltered under umbrellas recreate the feeling of Tokugawa geisha.

The apex of my stay in Kyoto was a late evening visit to Ninna-ji, a Shingon Buddhist temple founded in 888. My visit coincided with the Obon Festival, a three day celebration of the departed. As the sun set over Kyoto, huge crowds gathered at the base of the hill upon which the temple rests, all prepared with small messages and wishes to leave for their ancestors. At about 8:30pm, lights illuminated the temple structures and surrounding forest, and the visitors were allowed in to pay homage to the departed.

I have never seen a sight as breathtaking as the view from the highest structures of the Kiyomizu-dera complex just after sunset. The temple rests about halfway up a large hill, nestled delicately throughout the woods with an extraordinary view of downtown Kyoto. With every turn, visitors are greeted with an awe-inspiring vista set within an environment that encourages introspection and quiet meditation. I participated in as much of the festival as I could understand, drinking water from a wishing well and giving thanks for those who have gone before me.

My time in Kyoto was rounded out by an overnight stay in Ninna-ji, a Shingon Buddhist temple founded in 888. If you ever have the chance to visit Japan, I highly recommend staying in a temple. At Ninna-ji, I had my first Japanese bath experience (Japanese typically favor public baths over western showers), slept on a comfortable tatami mat on the floor of a large shared room, and awoke at dawn to witness the chanting of the Shingon monks in the main temple building. If I could begin everyday in such a meditative way, I have no doubt inner peace would follow throughout my day.

Up next, I will post about my experience visiting Hiroshima on the anniversary of the signing of the peace agreement between the US and Japan.

Labels:

Japan

Location:

Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Konichiwa from Japan!

I have arrived to the bustling city of Tokyo, where Red Bulls reign, and under-slept people can be seen catching naps just about everywhere.

On first impression, Tokyo was different than I had expected. The buildings are not skyscrapers, the city is more of an L.A.-like urban sprawl than a tightly packed Manhattan, and wi-fi, unfortunately, does not seep out of every building.

I stayed the first few nights in traditional wakan housing, a large room enclosed by shoji screens and floored with bamboo tatami mats. I shared the space with about fifteen other people, each of us sleeping on our own futon mat covered by a simple blanket. This style of sleeping is surprisingly comfortable, especially when the summer weather brings 95+ degree heats and thick humidity.

On first impression, Tokyo was different than I had expected. The buildings are not skyscrapers, the city is more of an L.A.-like urban sprawl than a tightly packed Manhattan, and wi-fi, unfortunately, does not seep out of every building.

I stayed the first few nights in traditional wakan housing, a large room enclosed by shoji screens and floored with bamboo tatami mats. I shared the space with about fifteen other people, each of us sleeping on our own futon mat covered by a simple blanket. This style of sleeping is surprisingly comfortable, especially when the summer weather brings 95+ degree heats and thick humidity.

My orientation program in Japan is run by the Harvard College in Asia Program (HCAP), a partnership that encourages collaboration between Asian universities and Harvard. Students from the University of Tokyo have graciously hosted me and my colleagues for the majority of our stay in Japan. HCAP encourages cultural exchange, so our first evening together, our Japanese friends performed a highly-choreographed, cross dressing-friendly dance routine. We returned the favor by teaching them how to duggie.

After a long day of lectures, several people took me out for my twenty-second birthday to a traditional sake house. I can’t say that I enjoy sake particularly much, but the Japanese among the group were very impressed to learn of the US invented sake bomb. It turns out, most young Japanese enjoy western cocktails, and sake is mostly enjoyed by the elderly.

I woke up at 4:30am today in order to make it to the opening of the Tsukiji fish market, Tokyo’s most famous open-aired market. Vegetarian-friendly food is hard to come by in Japan, and Tsukiji market may be one of the worst places to go for a noodle or tofu meal. I managed to find a place that served vegetable tempura for breakfast (Japanese breakfasts are full dinner-style meals) and was quite happy observing the bustle of the marketplace and nearby Shinto shrines.

Tonight, I am off to experience karaoke in downtown Tokyo and will then hop on an overnight bus to Kyoto. In the next few days, I will explore the city of Kyoto--one of Japan’s cultural gems--stay the night in a Buddhist temple, learn how to meditate from Zen monks, and visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)